Nauticam Fisheye Conversion Port (FCP): field review

Review index:

- Prelude

- Expectations and Impressions

- Sharpness and depth-of-field

- Color rendering and chromatic aberration

- Sunballs and reflections

- Split-shots

- Final Thoughts

- Recap: Pros & Cons

This review was first published in DivePhotoGuide, in February 2024.

Prelude

Reflecting on the various cameras and lenses I have used over the years, if I were asked to pick just one camera and one lens to go photograph the underwater world for a year, I would probably go for the good old Tokina 10–17mm fisheye mounted on my trusty Nikon D500. After all, I am a wide-angle shooter at heart, with a love for scenic reef shots and close-focus wide-angle (CFWA) imagery (learn this technique here).

The venerable Tokina didn’t offer the absolute best optical quality—far from it—but it stood out by being the only zoom-through fisheye, offering a very handy range of 180–100° in diagonal field of view. It also focused right on the lens, allowing the use of 100mm mini-domes, which was great for CFWA. Alas, there was no full-frame equivalent of that hugely popular lens. Both Canon and Nikon released modern, high-quality 8–15mm fisheye zooms, but they were designed to offer just two usable focal lengths on full-frame DSLRs: a frame-filling diagonal 180° fisheye at 15mm and a circular fisheye at 8mm. An equivalent of the much-loved Tokina in the full-frame realm never appeared, and I ended up keeping my Nikon D500 just for that lens, despite having purchased a full-frame camera.

It was only in 2023 that the apparent heir to the Tokina legacy materialized, when news of a new Nauticam wet optic emerged and prototypes began to circulate. This Fisheye Conversion Port (FCP), as the name suggested, was designed to turn a standard (rectilinear) zoom into a fisheye zoom—ostensibly with a field-of-view range on a full-frame camera similar to that of the Tokina 10–17mm on a cropped-sensor body. Given Nauticam’s track record for building quality wet optics, the FCP created quite a buzz amongst underwater photographers, fueled by enthusiastic comments from the lucky few who got their hands on the prototype. The actual product announcement came in January 2024, with the final specs and pricing of the FCP-1 revealed.

I would like to thank Nauticam for providing me with a pre-production FCP-1, for the purpose of field-testing and writing this review. The timing coincided with my visit to Lembeh Resort (North Sulawesi, Indonesia), where I was teaching as part of the CCiL2024 workshop. I first used the FCP in the Lembeh strait, then visited the two nearby Murex Resorts, for a chance to photograph Bangka’s lush coral reefs and Bunaken’s turtles population, special thanks to the three resorts for the opportunity to visit these three top dive locations in a single trip! Check their Passport-to-Paradise if you’d like to do the same.

Expectations and Impressions

The FCP-1 is a water-contact optic, meaning it is designed to optimize image quality, taking into account the transition between dry land (the inside of the housing) and the underwater world. It also expands the field-of-view of the original lens, converting a standard “kit” zoom into a zoom-through fisheye. This is achieved with a combination of six optical elements, the front one being a dome.

In 2017, Nauticam had demonstrated mastery of the concept by releasing the Wide Angle Conversion Port (WACP-1), a rectilinear lens that could give select 28–70mm zooms a 130–59° of field-of-view, while delivering stunning image quality, and letting users shoot wider apertures (about two f-stops) compared to a traditional rectilinear zoom and dome port setup.

The WACP-1 set the bar very high. Could Nauticam repeat the feat with the extra challenge of expanding the field-of-view towards fisheye territory?

Size, Weight and Handling

A bit larger than the prototype, the “final” FCP-1 is just a little lighter than the rather weighty WACP-1—3.2kg (7.05lb) vs 3.7kg (8.15lb). Both lenses have a similar diameter, and while the main body is much shorter on the FCP-1, the front dome is bigger and more curved. The FCP-1 is just a little shorter than the WACP-1: My rough measurement shows a 16mm difference in length (about 10% shorter).

Just like its bigger brother, the FCP-1 comes with an integrated buoyancy collar, which Nauticam says makes it 0.4kg (14oz) negative. In practice, I used the same amount of floats for the Nikon Z 24–50mm/FCP-1 combo as I use when shooting the Z 105mm macro lens behind a flat port, and my housing’s buoyancy was in the same ballpark—which is good news.

Interestingly, the front glass is about the same size as the 140mm glass dome, which is my go-to port when using the 8–15mm fisheye for CFWA. Overall, the FCP-1 is certainly more bulky than that 140mm dome, but the extra length comes with a handy advantage: more space to tuck in strobes very close to the dome, which makes the closest CFWA shots easier to light.

Zoom range

To be sure if a lens will play nicely with the FCP-1, refer to the the latest Nauticam FCP-1 port chart. Initially, it seemed that only mirrorless cameras and their lenses were compatible with the new wet optic, but the port chart has now been updated to add welcome support for the old Canon EF and Nikon F 28–70mm lenses—the go-to lenses used with the WACP-1—with the right extension ring(s).

For Nikon Z-mount users like me, the recommended lens to pair with the FCP-1 is the Z 24–50mm, while Canon RF shooters will use the RF 24–50mm, both very affordable kit lenses. These pairings result in a very usable 170–87° range of diagonal field-of-view. Sony shooters using the popular 28–60mm lens will enjoy a slightly extended field-of-view range (170–74°), while the Sony 28–70mm goes even further (170–62°).

My expectation with the FCP-1 was covering the Tokina 10–17mm range (180–100°), so I was pleasantly surprised to see Nauticam went further at the narrow end of the range, which is helpful for those shy or smaller subjects where the Tokina remained a little too wide. The FCP-1 doesn’t quite reach the 180° mark, but I didn’t encounter too many scenarios where this 10° difference mattered. Even more impressively, from a field-of-view standpoint, the FCP-1 covers nearly the full range of the WACP-1, while expanding much more towards the wide end.

A comparison of the field-of-view achieved with the FCP-1 and WACP-1 with some popular lenses.

| Converted field-of-view | |||

| System | Lens | with FCP-1 | With WACP-1 |

| Nikon Z mount full frame | Nikon Z 24-50mm | 170-87° | 130-83° |

| Canon RF mount full frame | Canon RF 24-50mm | 170-87° | 130-83° |

| Sony E-mount full frame | Sony 28-60mm | 170-74° | 130-69° |

| Sony E-mount full frame | Sony 28-70mm | 170-62° | 130-59° |

My pre-production FCP-1 showed a bit of vignetting at 28mm, but Nauticam assured me this has been remedied in the final production design, with a slight adjustment of the lens-to-camera distance.

Assessing Image Quality

As it became known to other photographers that I had a pre-production FCP-1 with me, the number one question I received, not unsurprisingly, was: “How is the image quality?” Answering that important question is what the rest of this review is all about—with a particular focus on image sharpness.

I want to pause and make a confession here: I don’t consider myself to be a pixel peeper. I care more about having the right focal length and magnification capabilities for my subject, rather than the very best image quality. If image quality had been my top goal, I wouldn’t have used the Tokina 10–17mm for so many years; there were other fisheye lenses that performed better optically, but they weren’t as versatile.

For this review, however, I have been scrutinizing various parts of my photos, zooming to 100% and dissecting hundreds of images. There were times when I found image sharpness below expectations, paused to give my eyes some rest, only to come back and realize that the level of detail was actually adequately good—at a normal viewing distance!

As you read the following sections of this article, you’ll find my qualitative opinion on whether the image quality is meeting my needs, and the issues I’ve noticed. I have included numerous 100% crops so that you can also make up your own mind. People get confused with the meaning of a 100% crop, so make sure to check the box below.

One last caveat: This review took place in North Sulawesi, Indonesia during rainy season, when the water wasn’t at its clearest. Visibility ranged from about 18 to 30 feet (6 to 10 meters) in Lembeh, and perhaps 45 to 60 feet (15 to 20 meters) in Bangka and Bunaken. If you were to shoot the FCP-1 in the Cayman Isands and had visibility of 100 to 130 feet (30 to 40 meters), you would expect images to be sharper in the distance, due to lower levels of floating particles diffusing light.

Interpreting 100% Crops

The full-size images in this article measure 1200 pixels on the longest side; the same goes for the 100% crops. These were produced by cropping my Nikon Z9’s 46-megapixel (8256×5504-pixel) photos down to 1200×800 pixels, a very small fraction of the original image. Thus, each pixel of the 1200×800-pixel image matches exactly one pixel from the full-size image—this is the definition of a 100% crop.

That 1200×800-pixel image is intended to be viewed at its full size on your screen. If you’re using a full HD screen (1920×1080 resolution), the 100% crop will occupy a large portion of your display. If your screen has a 3840×2160 resolution, the 100% crop will occupy only 11% of your screen area, and that’s how it’s intended to be viewed. Don’t be tempted to zoom in: Your computer (or phone) will start creating visual artifacts that are not from the original image. I bet you rarely look at your own photos this way, so make sure to compare apples to apples if you want to see how the FCP-1’s images stack up against those taken with your current equipment.

To make sure you’re viewing one of the below 100% crops at a 100% ratio, simply download it on your computer and display it with your go-to image viewing software. If you prefer to look at a complete image, you’re welcome to download a few JPEGs of my FCP-1 shots at full resolution (8256×5504). For obvious reasons, I never make full-resolution images available publicly, so they are in a password-protected gallery: enter your email through this form and you’ll receive access details.

Sharpness and Depth of Field

While the WACP-1 turns a 75° field-of-view (28mm in full-frame equivalent terms) into a 130° field-of-view, the FCP-1 reaches the 170° mark and yet is both lighter and smaller. Thus, in terms of versatility and portability, the FCP-1 offers clear advantages over the WACP-1, but I was very curious to find out how the FCP-1 performed in the field, in terms of image quality—whether the FCP-1 exhibited the same impressive sharpness across the frame as the WACP-1.

Overall, I was very happy with the image quality of the FCP-1, as long as I closed down the aperture to at least f/13 or f/14 on my Nikon Z9 with the 24–50mm lens. It’s not that the FCP-1 isn’t sharp at more open apertures. I shot it at f/8 and noted the lens could resolve fine details, making good use of the Z9’s 46MP sensor. However, at that aperture, I found the depth of field to be too shallow, where important parts of the scene or subject were slightly out of focus. Obviously, this varies with working distance and focal length, but as I pixel-peeped at my FCP-1 photos, f/8 just seemed a little too open.

In the following, we’ll look at various examples, accompanied by 100% crops, so you can judge for yourself.

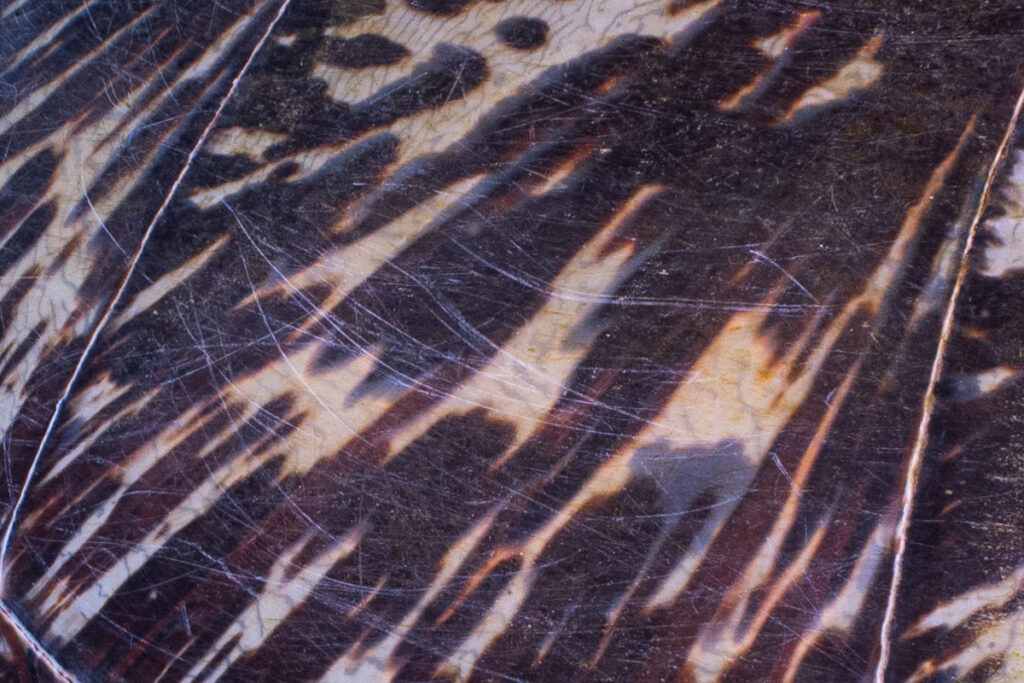

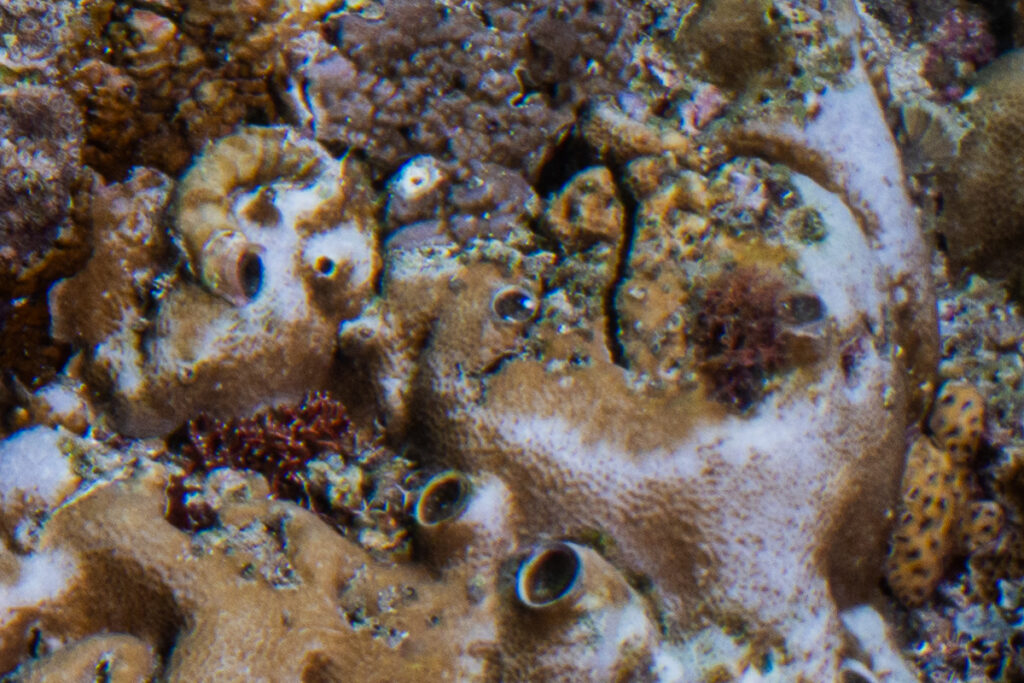

One annoying reality of in-the-field sharpness tests is that they are very much subject dependent: You typically need texture with fine details on the subject to judge how sharp your lens really is. So here is another f/8 example with different subject matter, slightly more zoomed-in.

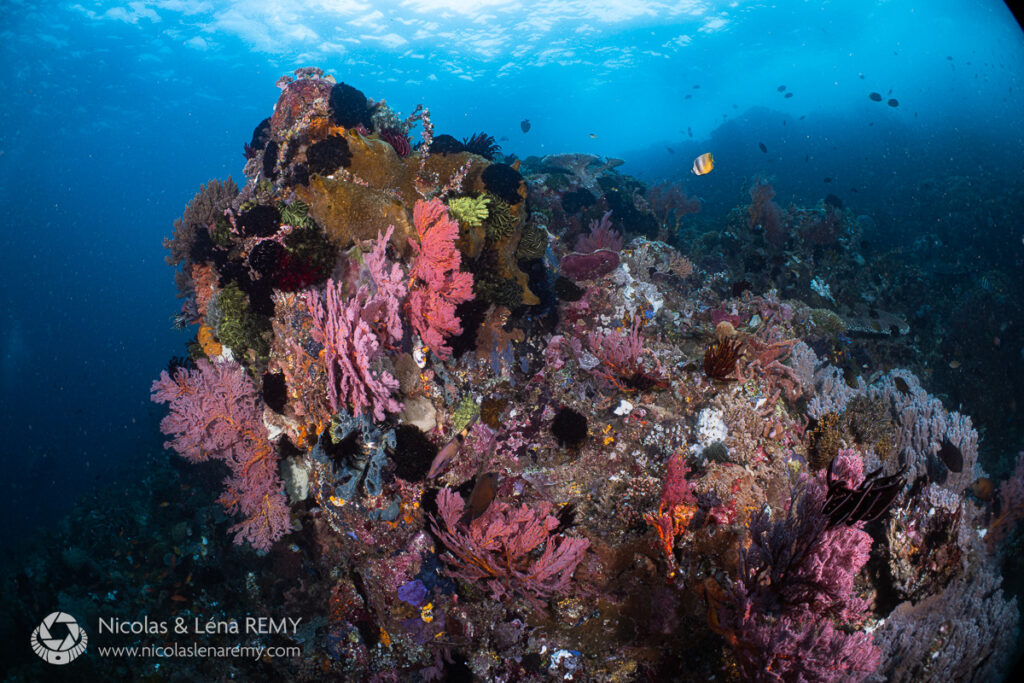

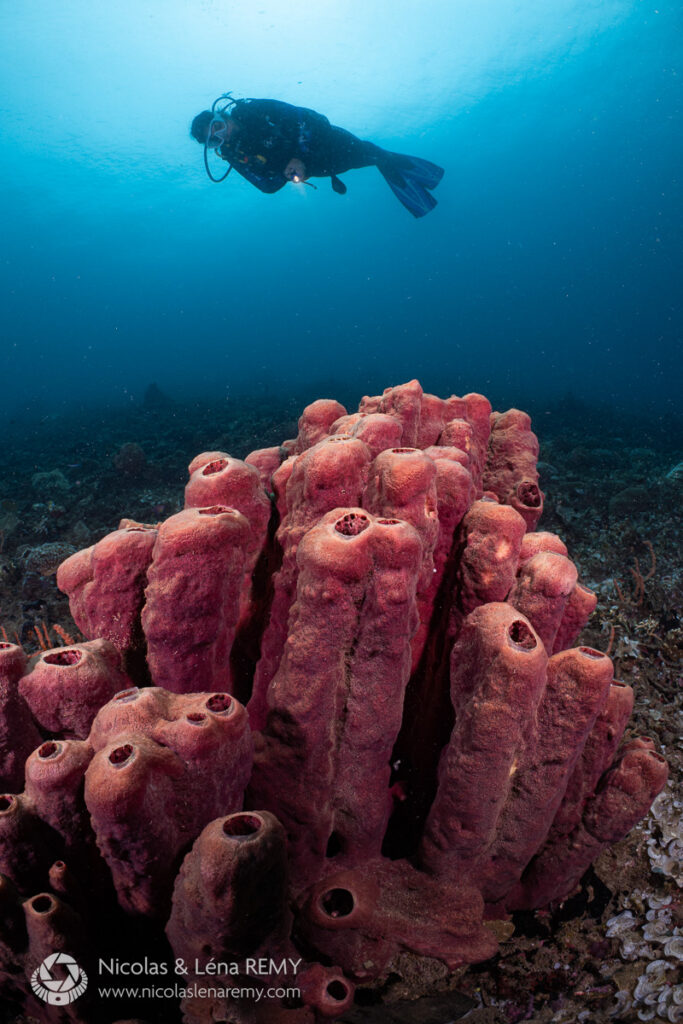

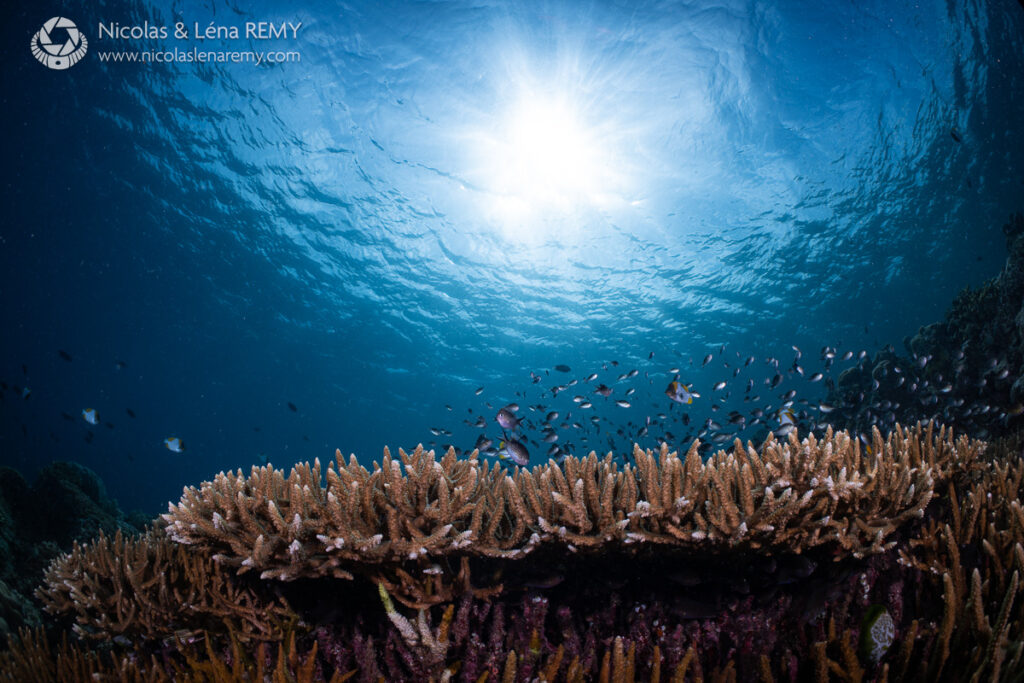

After a bit of experimentation with the FCP-1, I found f/13 and f/14 to be my go-to apertures for general wide-angle photos, including large scenes, as the following examples show.

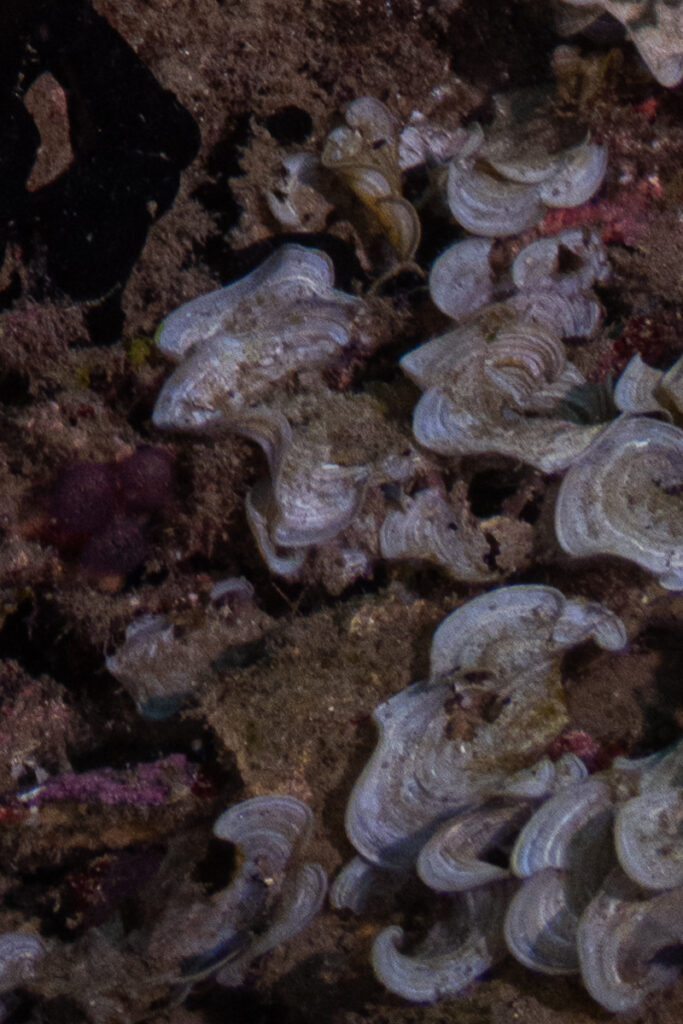

As we know, the closer you get to your subject, the shallower the depth of field, everything else being equal. So let’s look at another f/13 example, where I am much closer to the subject.

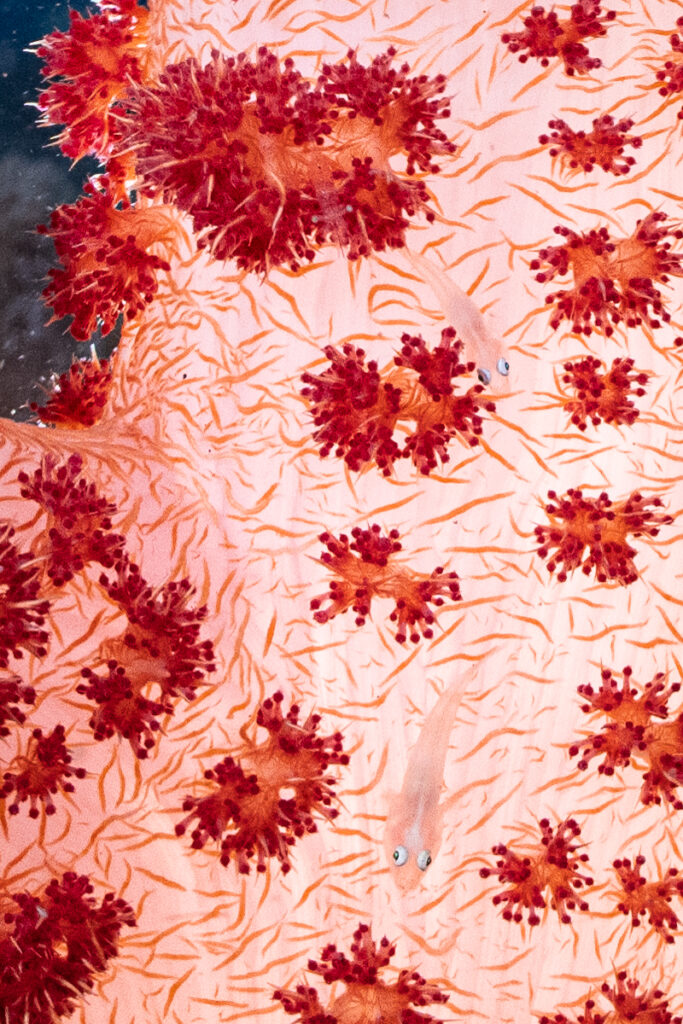

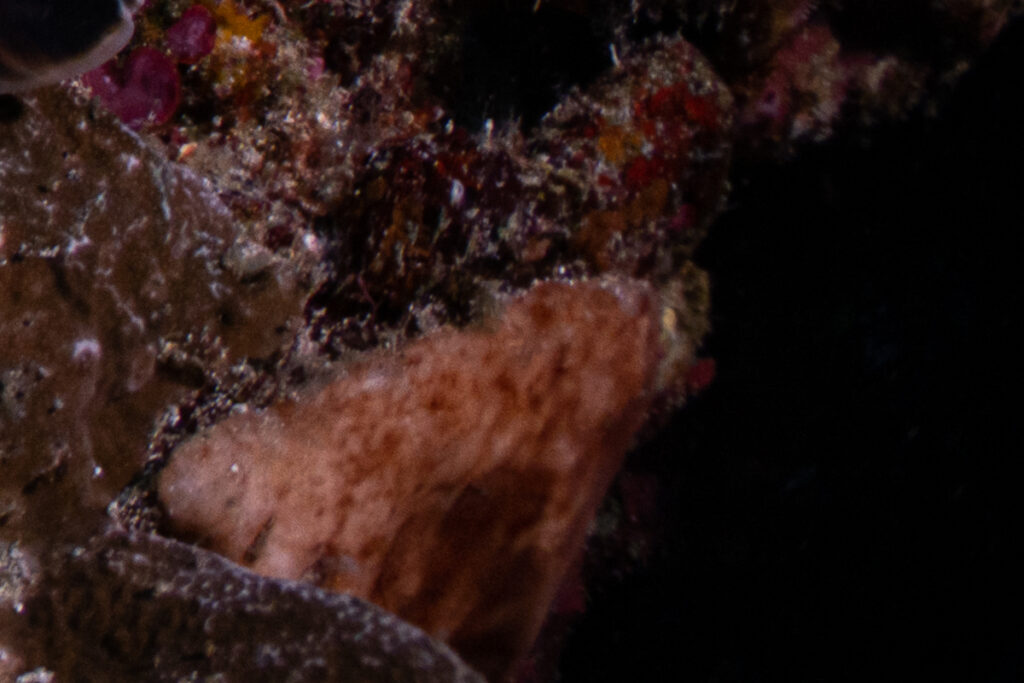

For true CFWA imagery with the FCP-1, when you want to make a small subject look big and detailed, I found f/16 to be a safer starting point in order to ensure the foreground subject was fully sharp.

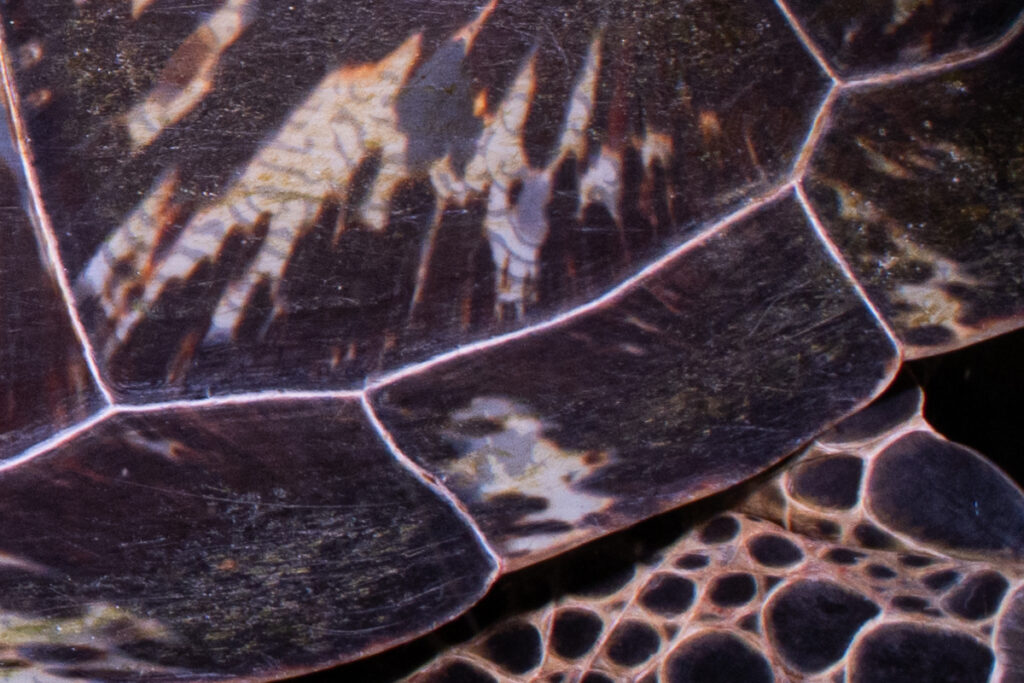

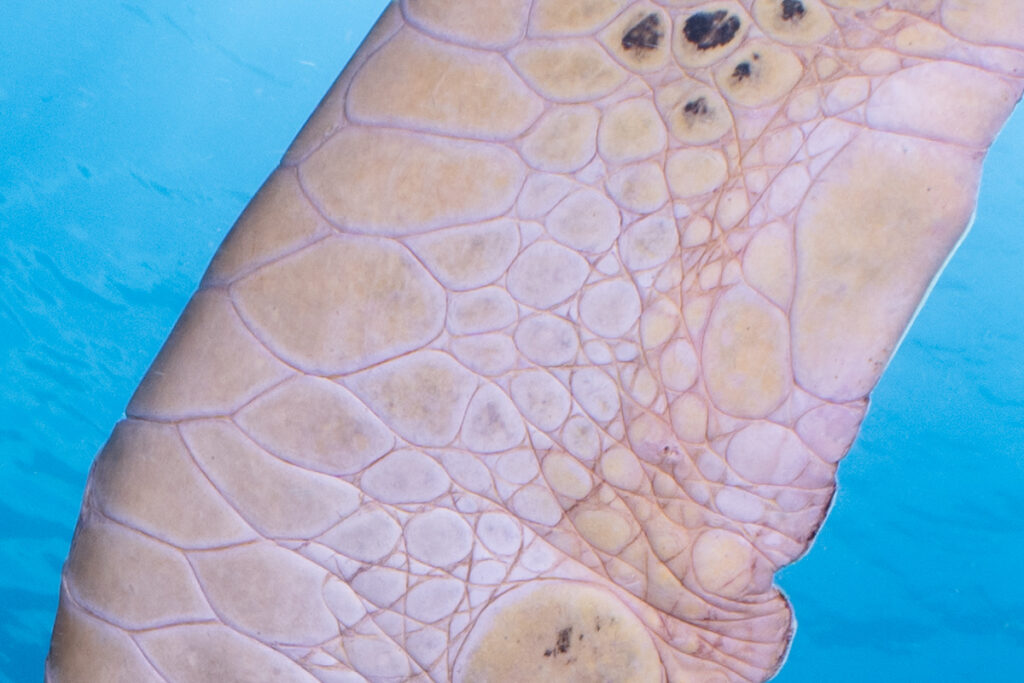

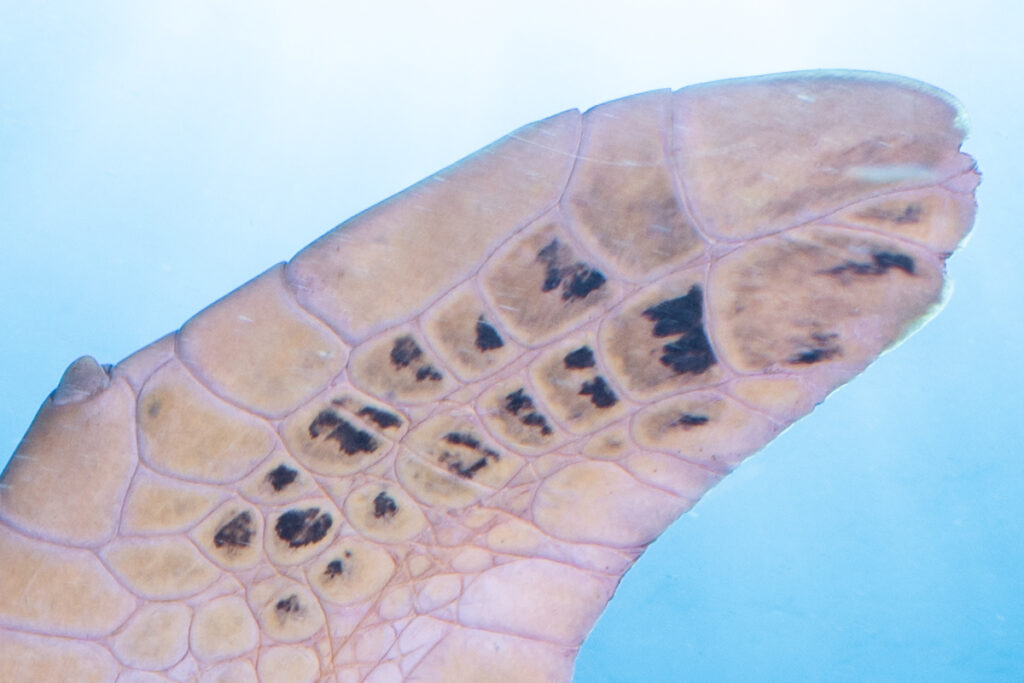

I don’t mind CFWA images having some out-of-focus areas, as long as this isn’t making the image less “readable.” The following is another CFWA example where I zoomed out and focused very close to the lens, nearly touching the turtle.

To finish this section, here are two extra shots, at different focal lengths, to illustrate corner sharpness.

In summary, I was happy with the sharpness of images produced with the FCP-1, as long as I closed the aperture down to f/13. I chose f/16 to f/18 if the scene required more depth of field, or when I was within touching distance of the subject. Conversely, I opened up to f/11 for subjects swimming in midwater. Overall, the FCP-1/Nikon Z 24–50mm combination made good use of the 46 megapixels of my full-frame sensor, producing image quality light years ahead of the Tokina 10–17mm. In terms of depth of field, the FCP-1 doesn’t offer quite the same advantages as the WACP-1. I found that I needed to close down the aperture as much as I would with a 8–15mm/140mm dome combo—sometimes a half or one f-stop more.

Colour Rendering and Chromatic Aberration

When I started shooting the FCP-1, I used auto white balance, which resulted in a green color cast, not as intense as I reported in my EMWL-1 review, but still noticeable.

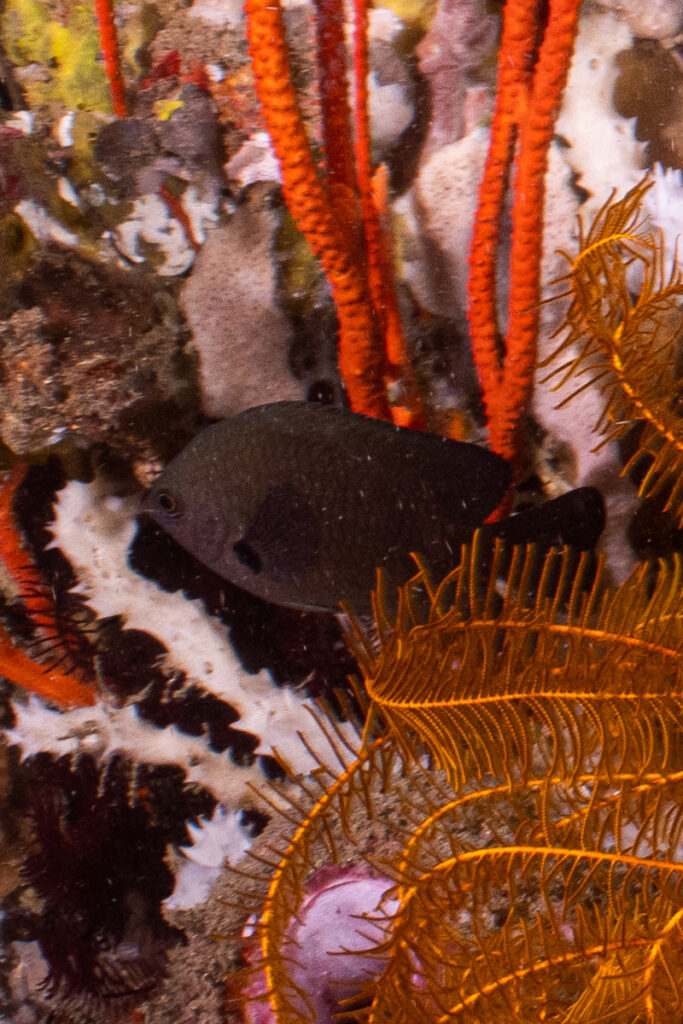

Once white balance was adjusted (obviously, you want to shoot in RAW format), this became a non-issue, and the FCP-1 was excellent at rendering all sorts of colors, from the yellow bellies of Bunaken’s turtles to the pink or green or orange corals of Bangka Island.

Also, I didn’t notice any chromatic aberration (color fringing) despite shooting some high-contrast underwater scenes with the FCP-1. (This was an annoying aspect of shooting the Tokina 10–17mm.) However, I did see some chromatic aberration on the topside part of my split shots; scroll down to the over-unders section for details.

Sunballs and Reflections

A common issue when shooting with a wide-angle lens into the sun is the appearance of flaring, or worse, seeing reflections of the lens in the dome port, and I wanted to see how the FCP-1 fared in that respect. At depth (30 feet, or 10 meters, and over), I didn’t encounter any reflections or flares whatsoever when shooting sunballs.

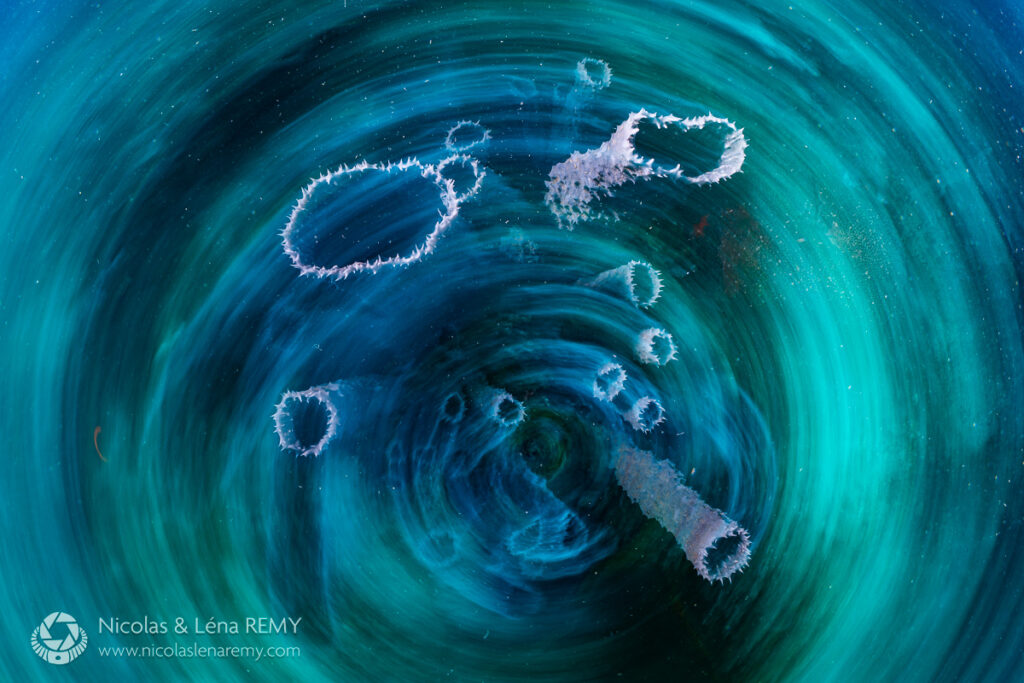

When shallower, typically at depths where Snell’s window is visible, reflections appeared at times in the form of clearly defined circles, when I was shooting straight into the sunball. That being said, I rarely shoot the sun this way: I’d rather have some subject matter partially blocking the sun—diffusing the light and taming the hot spot—or I’d leave the sunball just outside the frame, letting only the sunrays peek in. When following either of these approaches, the FCP-1 produced no reflections at all.

Back home in Sydney, Australia, I went shore diving during the Cole Classic Ocean Swim event in Manly. Alas, the water was murky that day (visibility of about 12 feet, or 4 meters), but the many swimmers provided plenty of subject matter for some Snell’s window shots.

Split Shots

Water-contact optics and wet lenses are known for being poorly suited to split shots (over-unders), but I was curious to see if the FCP-1 was any good for that type of photograph. A larger dome port (8 inches or more) is preferable for split images as it helps to control the waterline, but I don’t mind using a dome as small as the FCP-1’s front glass (roughly 5.5in/140mm), as long as the sea isn’t too choppy.

As a reminder, for splits, you can’t focus on any topside element or the underwater portion of your image will be out of focus. Instead, you lock on to your underwater subject, and close the aperture down more than you would for typical wide-angle work, so that the topside portion feels sharp, too (though, in fact, it’s not always fully sharp).

Below are a few test shots taken with the same model focus distance (manual focus on my fin underwater) but varying the distance of the boat in the background. Overall, despite closing down the aperture to f/22, I found the top part of the image to be a little too out of focus for my taste. A traditional fisheye and larger dome port produce better topside sharpness.

That being said, if the top portion for the image doesn’t hold important details and is there to give context around the underwater portion, then I don’t mind that area being a little soft. If I were planning a wide-angle trip where split shots were not the main goal, I would happily leave my big dome and fisheye lens at home, and just use the FCP-1 for the occasional over-under.

One last comment on splits: You may have noticed some slight color fringing in the topside section around the man in the first image, and around the windows of the boat in the second image. However, this can be easily removed during post-processing; see below.

Final Thoughts

With the Fisheye Conversion Lens (FCP-1), Nauticam has made a water-contact optic that works with a standard zoom to produce a lens many wide-angle shooters have been dreaming of: a zoom-through fisheye that leverages the high resolution of modern full-frame sensors.

Whilst the FCP-1 doesn’t provide the depth-of-field advantage of the WACP-1, its much extended zoom range allows it to cover a variety of subjects, from big animals, wrecks and reefscapes to smaller marine life like lionfish and potentially smaller critters, since you can focus very close to the front glass.

So which one is better: the FCP-1 or the WACP-1? From 130° field-of-view and narrower, the WACP-1 offers greater depth of field at more open apertures. At the same apertures, this makes images shot with the WACP-1 look more detailed than those captured with the FCP-1. At such fields-of-view, I prefer images produced by the WACP-1, which also allows me to shoot my strobes at lower power (provided I don’t hit my camera’s maximum sync speed).

While I love shooting the WACP-1, its 130° field-of-view becomes limiting with the biggest subjects or when I want to include more in the composition. The FCP-1 gives you access to these wider angles, while letting you zoom nearly as far as the WACP-1 when a shy subject shows up. As a bonus, you can use the FCP-1 for split shots, if you can live with the topside portion being a little soft. For me, flexibility is worth more than getting the very best image quality, so my vote goes to the FCP-1.

If you invest in an FCP-1, can you ditch your trusty 8–15mm fisheye? If you love shooting splits in choppy seas or if you like your over-under shots to tell a story where the topside subject matter is as important as what is underwater, then a traditional fisheye and large dome port are hard to beat. If you’re only an occasional splits shooter, I bet your traditional fisheye will sit on the shelf for good. When paired with a 14mm prime or 14–30mm/14–35mm zoom lens, the FCP-1 is even capable of producing circular fisheye images—sadly, something that I didn’t have time to test.

Now for the million dollar question, or rather $6,941 question: Should you buy one? That’s a decision I can’t make on your behalf, but here are a couple more considerations to help you decide. On the “yay” side, the FCP-1 is the only lens which truly covers the whole spectrum of wide-angle photography (fisheye, CFWA and mid-size fish portraits) while leveraging the resolution of your modern full-frame camera sensor. I have compared my FCP-1 images with those of my Tokina 10–17mm/D500 combo, and the former are significantly more detailed. On the “nay” side, despite the high price tag, you don’t get the very best wide-angle image quality out there. If you’ve been shooting the WACP-1, you’ve seen just how high the bar can be.

The decision comes down to what matters most to you: getting the crème de la crème in image quality or having the most versatile wide-angle optic? If you’re like me and used to have your Tokina 10–17mm glued onto your cropped-sensor DSLR back in the day, then you were already choosing versatility over image quality. There have always been better (fixed) fisheyes out there; they just didn’t cover as many subjects.

I am of the opinion that a good wide-angle shot is best appreciated on a big screen or large print, seen as a whole, rather than pixel-peeping at 100% zoom on a laptop. You’ve probably guessed where I stand: If I were going on a wide-angle trip with just one lens, it would be the FCP-1.

Pros & Cons

Pros:

- Liberating zoom range from 170° fisheye down to a near-fish portrait field-of-view;

- sharp optic capable of leveraging a modern, high-resolution full-frame sensor; focuses very close to the dome;

- excellent color rendering, free from chromatic aberration;

- usable for splits, if you accept a little softness in the topside portion;

- well-controlled reflections, unless you’re shooting straight at the sun in the shallows

Cons:

- Aperture needs to be closed down to at least f/13 for sufficient depth of field;

- heavy price tag

About the author

Nicolas Remy (@nicolaslenaremy) is an Australia-based pro shooter, founder of online underwater photography club & school The Underwater Club, and Nauticam ambassador. His images have been widely published in print and digital media, and have won over 35 international photo awards.

Comments